A motley bunch of self-inspired professionals came together last week in Chandigarh's Sector 17, angry at the rape of a girl by five cops of Chandigarh Police. For five hours, they talked. FIVE HOURS. Five hours that redefined the idea of a protest. Many of them belonged to the media, but they refused to ask their friends in the media to cover the dharna. Their aim was different. They wanted to talk to the city. They wanted to listen to the city. This is a brief reportage from Ground Zero.

Nischay Pal

For years now, I have been watching one or the other interest group sitting on a dharna in Chandigarh's Sector 17. In most cases, the dharna would have a life of its own, an island amidst a sea of shoppers and casual strollers in the plaza. A group of 4-14 people would sit on a durrie, a couple of quick-printed A3 size posters announcing their demand, a bunch of press photographers would arrive on the scene since someone from the dharna-group had would call and request for a photograph.

Next to the fountain atop a tasteless cemented structure that would have as much water as the signs of having suffered the vagaries of weather in its short life of half a century, the dharna-group would become astonishingly active with the arrival of the lensmen from various newspapers. "Zindabad - Murdabad" would reverberate through the air. One enterprising man would pick up a poster and hold it aloft in his hands. With their template photographs clicked, the golden silence would return. The grateful agitationists would request the "press photographers" to have a cup of tea from a nearby kiosk. "You have a press release, too?" a photographer would ask. "Shaam nu bhej devange ji," he would be told. Job done. Agitation over for the day, with enough time left for lunch. The highest display of responsibility would be about who rolls the durrie and keeps it in his car.

Agitation-protest-dharna-morcha-opposition-murdabad-zindabad-fight for a cause – jo hunm se takrayega – hamari maange poori karo – kender sarkar hai hai-punjab sarkar murdabad – inkalab –shaheed bhagat singh – better wage scale on 8-14-20 basis – vocational teachers-berozgaar ETT teachers-anganwadi workers-cpi-cpi(m) – falana group-dhimka group.

This was such a beautiful mould of agitation in Chandigarh. Every step time tested. Every day fruitful. After all, the next day's newspapers do carry that picture. The raised fist. The anger on the face. The Hamari Mange Poori Karo poster. And under the great umbrella of a big banner, what they ostensibly think is in the mould of RK Studios or Raj Shri Productions -- Lok Sangharsh Morcha, XYZ Employee Union (Regd), or whatever other platform they gather on.

In 65 years, I have not seen a train coming on this platform.

I wanted to watch this up close and personal. So, one fine day when there was a nip in the air, and the sun seemed generous, I decided to hog a spot in the town plaza, yards away from a group of 43 teachers sitting cross legged on a rug. The 44th was on the mike. "Sathiyo...". The man seemed fairly adept at his business. The speech came to him as second nature. He was talking about promotions being blocked, wanted ban on contractual recruitment of teachers and said his and his associates' prime purpose was to safeguard the school system.

Hundreds of people were filing past them, not one paid attention, not one sat with them for a minute, not one asked why were 44 men (there were no women) so angry that they had left everything to sit in a protest in the town square.

"Poori karo!" "Poor karo!" Suddenly, the group was super-animated. I could not fathom what demand it was that they wanted fulfilled. And it was then that I saw five people lurking nearby, with suspiciously bulging black duffel bags slung from their shoulders. Out came their cameras, quickly they snapped the action. Game over. In the next five minutes, everyone had vanished, and I was left to admire the role that the plaza plays in the city's discourse.

Next day, the photograph duly appeared in virtually all the newspapers. Clearly, various interest groups have perfected the dharna technique.

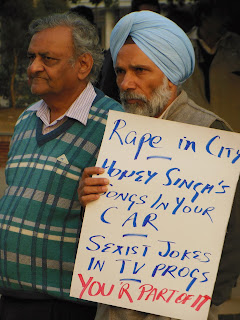

Last week, when news appeared that a minor girl was raped by five policemen repeatedly over a period of several days, a few inspired souls thought there should be an expression of outrage, a display of anger, a mark of protest, a voice of the city, an exhibition of solidarity with the victim. With affiliations too loose and no worked out networks, getting a bunch of people together at one selected spot in the town at a pre-determined point was a task too easy and too difficult at the same time. What would be the demand? Should they have a banner? How else does one protest? May be they can grab a piece of paper and scrawl a shrieky slogan on it, hold it aloft, and shout a Murdabad – fist clenched, air punched?

How do you protest in a world that has become so noisy?

In a particularly weak moment, I thought it was no use punching the town square air with your fists. I knew the fate of 44 teachers. Not the parents of a single child had cared to join them; instead, many had preferred to buy a pair of chappals from the discount sale at Sant Shoe Store nearby.

The 44 teachers were equally pissed off with the media, but they couldn’t afford to say that in their press release. They couldn’t afford to annoy the photographers by even hinting at how much space the media gives to genuine issues of the people. Of course, the issue figures in their own discussions, but not in the press release.

But some people just do not get tired. A sociology professor from Panjab University, who is there in the chowk, in a TV studio, at a dharna in the university, at a meeting in Gurgaon, every time you bring a people-connect issue to the fore. A former registrar of a medical sciences university who belies age and successfully connects to the young, his anger and logic both intact. A journalist who straddles the world of media, activism and politics with equal aplomb. A film maker who dabbles in television but manages to debunk the dumbing down theory. Each brings his friends, too. A lawyer who recently turned into an Aam Aadmi Party leader but whose ability to critique has not weakened in his new avataar. One call and they all find time to land at the chowk. They always manage to do so. They have routines, vocations, families, and still rejig priorities. A Thapar University don drove from Patiala the other evening to be part of a slogan shouting group at the PU, and then stayed back to intently listen to the young student leaders of the PU.

It was a Friday, and Sector 17 plaza is on any day a hustling bustling place. The group was soon into a routine – Murdabad, Zindabad. A few slogans directed against the police, another few towards the administration. Chandigarh Prashaasan Murdabad. Insaaf. And also, that old redoubtable made a re-appearance – Inquilab Zindabad.

And then the lawyer-turned-politician turned into a quick thinking strategist. He went next door into a shop and bought/brought a megaphone, microphone in hand, the loud speaker hanging from the shoulder. Powered by eight dry batteries and drenched-in-passion spirit, the motley group soon had a voice. A louder voice. MURDABAD...ZINDABAD...INQUILAB!

And then it all turned altogether on to a different track. Something happened to the dharna. Panjab University academic, Janaki Srinivasan, who makes extremely nuanced arguments in political science, was on that megaphone. The group had now grown to some 500 people, Janaki in the centre, mike in hand. She was explaining deeper and complex notions of patriarchy. To the people in the chowk? Yes. Next, it was Daljit Ami's turn to take over. Dharnas have a grammar, set by decades of professional dharna masters. Daljit respects few stereotypes. He thought chowk is the place for a serious discussion. He is like that. He even thinks TV studios are a place for seriously approaching complex issues instead of dumbing down these. Something unnerving was happening in Sector 17. The 500 odd people were seriously listening to Daljit Ami as he explained why we should not call the rapists, beasts. "Beasts do not rape, men do. Nature has no role in it. Nature does not make these men. Our society makes men rapists." Oh My God!

Bravery has many forms, but trying to get a serious dialogue going in the chowk would have seemed foolishness to me. But then, were the braves not often called foolish all through human civilisational experience?

Off and on, slogans kept cajoling new people to join the crowd. So a student from Panjab University thought of raising what he thought was the most meaningful slogan – “Pittri Satta Murdabad.” A couple of journalists in the chowk seemed very confused. This was the first time they had heard of such a slogan. Whatever happened to the classic dharna they were used to covering?

"Rape is not a crime against women." Now, I thought this one was certainly new, and one that will make the women in the crowd, though hugely marginal presence, take out their slippers and beat the hell out of the speaker. "This is deliberately reducing the intensity of the crime. When a woman is sexually harassed, is it not a problem for her husband, her father, her boy friend, and if you have a heart, yours? Rape is a crime against humanity. Every rape is a rape of the kind of society you wanted your children to have." And people were listening.

"Rape maa ki gaali se shuru hota hai."

"Start questioning your dad. It starts from home."

"If you fail to stand up, YOU murdabad."

I wanted to feel offended, but then thought of all the times I did not stand up. I felt so Murdabad.

"For every weak moment in my life when I did not stop because I felt I was outnumbered, and those harassing the girl were a big group, mujh par bhee laanat hai." Was this man speaking about me?

The group was talking to itself. It was speaking to the city. The city was talking to itself. This was a dialogue in the metropolis.

"Do not remain silent, Nirbhaya is watching." The poster was enough to break through the hestitation. "Rape is a crime; Silence is Rape # 2." Now, that made it difficult not to rise to the sloganeering bunch's call. "Aap naare ka jawab nahi do ge tau hamaari awaaz dab jaye gi." This group was not even saying they are a power. They were saying they were weak.

A policeman called me aside. “Sir ji, yeh mat samjhiyo hum aap ke saath nahi hain. Ghar par to hamaare bhee yahi baa thee ho rahi hai.” For a moment, I was tempted to count the cops also among our listeners.

Every now and then, slogans would take over. And then, a new slogan pierced through the hearts. "Sawaal Kar..Sawaal Kar". Question what? "Satta par sawaal kar," "Political parties par sawaal kar," "Media par sawaal kar," "Sampadak par sawaal kar." We were all responding with full gusto – "Sawaal kar, sawaal kar."

Then, the questions started becoming difficult. "Khud par sawaal kar," "Maa par sawaal kar," "Baap par sawaal kar."

But then, they seemed easier compared to what was coming next. "Phir sawaal par sawaal kar," "Phir jawab par sawaal kar," "Har baat par sawaal kar," "Har jawaab par sawaal kar."

Daljit Ami was on the loose. And he had got the pulse

of the people. It had already been four hours, four non-stop hours of a city talking to itself. There were moments in between when the crowd would dissipate, we would be left down to 100 odd people. A few slogans would again bring a bunch of fresh faces, all gathering around. There was no discipline. Who is to speak? For how long? Contradictions were aplenty.

"Women bodies are being commoditised. Look at our advertisements, how they denigrate women," someone who had got the megaphone was saying. Soon, the next speaker was slamming him: "When the answer is that simple – NO – which part of it confuses you? N? or O? No means no. The height of the skirt has nothing to do with it. Do not talk of their clothes. They rape the burqa clad ones, they rape infant girls, they rape matronly old women, they rape literally insane women in homes for mentally retarded. So stop this argument about what women should wear."

The mega phone had changed hands -- "What do you mean by saying 'They rape.'?" Rapist does not come from outside. And he pointed out to another poster.

"Next rapist will not come from the police. He will come from mine or your family, or our street, or the street next to it."

A lot of Chandigarh cops looked on, anger writ large on their faces. Few thought it was because five of their ilk had shamed them. Most thought the Chandigarh Police Murdabad sloganeering was enraging them. Meanwhile, another speaker was on the mega phone.

"Naak hamari bhee kaati huyee hai -- Aap ke paanch pakre gaye hain, hamaari bradari ka chamkta heera ghatiya kola nikla hai, Tarun Tejpal ne patarkaari ki naak kaat hai. Yeh larrayee naak bachaane ki hai."

Students from Kendri Gurdwara Singh Sabha also said their piece. “Our teacher said go and join the voice of the people,” one of them said. A young PU student, Divya, was angry that the debate explodes in the town square only when a rape happens. “What about my daily life? I step out from my home, walk through the market, go shopping, search for groceries... male gaze panning my every moment.” I was looking a little farther away, a young couple going hand-in-hand, a score pair of eyes following them.

By now, five hours had passed. The conversation was not stopping. It took some quick thinking on the part of Prof Manjit Singh to ask Ekam Moonak, a youngster with a mellifluous voice, to sing a song, and people joined in. The song was a perfect end to the dharna, to a dialogue, to a conversation.

This was a dharna? At times, I felt this was a seminar out in the chowk. I noticed Prof Meera Nanda (The God Market) standing at the edge of the crowd. I saw Prof Kuldeep Puri diligently watching every mood of the crowd. The few moments for which he spoke, I thought a sage has come to the town square. Prof Akshay Kumar took to the mike and seemed worried that in the broadspectrum of issues from Soni Sori to Manipur Manorama Mothers to Irom Sharmila to the state using rape as a weapon of intimidation and humiliation, we must not take the pressure off the Chandigarh Police. Rajiv Godara kept his counsel, watching everything, aware that talk about Aam Aadmi Party was happening on its own. Sarbjit Dhaliwal of The Tribune hung around for a long time. Khushal Lali, another inspired journalist, was there, too. “We are from Pukar, please always call us for such a cause, we will be there,” a bunch of youngsters were telling me about their NGO. “Why didn’t you call Tarlochan Singh of Punjabi Tribune? He is the one who writes really wonderfully about genuine issues?” Tarlochan is a friend; I was happy he was Zindabad even when absent. “Where’s Hamir Singh? How come he is not here?” someone asked me accusingly, as if I was guilty why one good man was less. “He was here most of the day, and he was an inspiration to us for even thinking of gathering here,” I responded. “Bande hee gine-chune ne ji shehar vich!” another piped up.

“Dhhayee totru.”

But I was thinking about this dharna and the dharna of the 44 teachers.

Only one of them could be called a dharna.

It is time for all of us to do a re-think. We have tried for decades those sit-on-a-durrie, raise-a-few-slogans, get-a-photo-clicked, issue-a-press-release dharnas. And we have tried this – no photos, no press releases, no durrie. A conversation with the city. A dialogue among ourselves. Prof Manjit Singh calls it Lok Awaz.

That's perhaps because there were 'Lok' in it, and they heard their 'Awaaz'. It has to be more intelligent than MURDABAD-ZINDABAD-INQUILAB.

That's the only way to ensure that somethings remain Murdabad, others Zindabad, and one day, we have an Inquilab.

Sawaal Kar... Dharna Par Bhee Sawaal Kar.

P.S. A journalist friend from Jalandhar suggested that the piece is perhaps too long, but then, when asked why should writers fall into media-induced word limits, agreed, saying, "Word length par bhee sawaal kar." The chowk is reaching across, friends.

No comments:

Post a Comment